Ten years on, the memories still sit heavy. Paris has rebuilt, healed in parts, and kept moving, but the scars from the night of November 13, 2015 haven’t faded. What happened that evening wasn’t just another tragedy in a world that has grown used to grim headlines. It was a coordinated attack that ripped through the heart of France and reshaped its sense of security, identity, and collective grief. Many still describe it as the country’s 9/11.

A Night That Changed France

Here’s the thing: the attacks unfolded with a level of coordination and brutality that stunned even seasoned investigators. Within minutes, suicide bombers detonated themselves outside the Stade de France, gunmen ambushed café terraces across the city, and three attackers stormed the Bataclan concert hall. By the time it was over, 130 people were dead. Two survivors later died by suicide and have since been recognized as victims, bringing the total to 132.

To understand how deeply this shook the country, you only need to revisit the images: concertgoers climbing out of windows to escape gunfire, restaurant tables overturned on blood-stained pavements, police sprinting toward danger with little idea how many attackers remained.

A senior French counterterrorism official told Le Monde at the time that investigators had “never witnessed an operation planned with such precision on national soil.” That assessment has held up over the years.

Voices of Remembrance

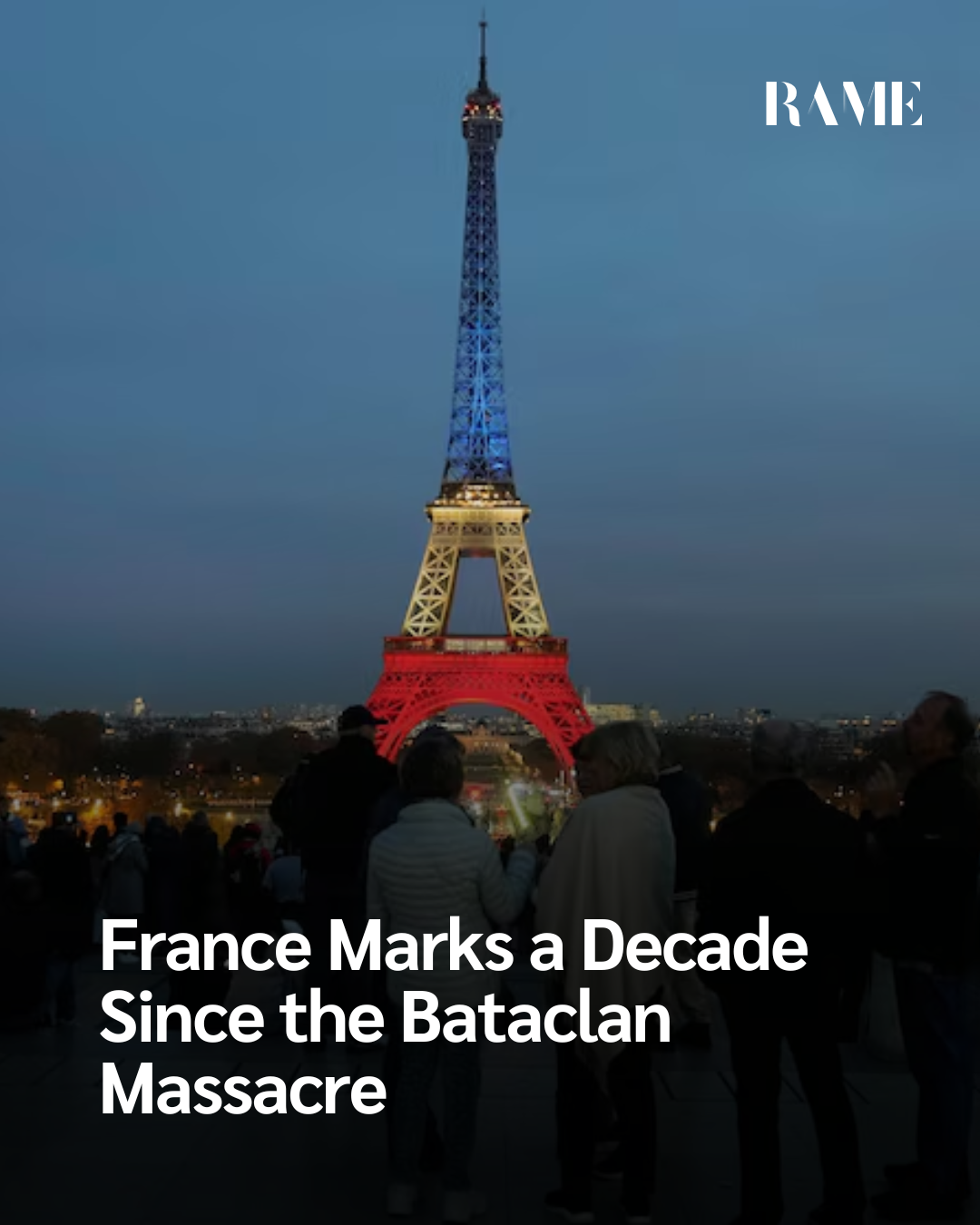

On Thursday, President Emmanuel Macron and First Lady Brigitte Macron joined Sophie Dias at the Stade de France for the first tribute of the day. Dias’ father was the first person killed that night, and she stood again at the stadium gate where he fell.

“We are told to turn the page,” she said. “But the absence is immense, the shock is intact, and the incomprehension remains. I’d like to know why; I’d like to understand. I’d like these attacks to stop.”

Macron echoed the sentiment in a post on social media, writing that “the pain remains” and that France remembers “the lives cut short, the wounded, the families, and the loved ones.” Throughout the day, he traveled from Saint-Denis to each attack site: the Carillon and Petit Cambodge, La Bonne Bière, Le Comptoir Voltaire, La Belle Équipe, and finally the Bataclan, where 90 people were murdered.

A security analyst from the Institut Montaigne summed up the national mood: “Commemoration is not routine. It’s a way for France to show that these victims are part of our national story, not just a tragic headline from a decade ago.”

The Long Road Through Justice

It took nearly seven years before the main trial concluded. In 2022, Salah Abdeslam, the only surviving member of the original cell, was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole, the harshest penalty under French law. Nineteen others were convicted for roles ranging from logistical support to planning.

Legal scholar Camille Aumont noted in an interview with France Inter that the trial “forced the country to revisit the trauma in granular detail but also helped many families reclaim part of the narrative.” The courtroom became a space where victims, survivors, and relatives could testify publicly about what they had lived through.

Memory, Culture, and the Work of Healing

Since the massacre, France has built an expansive ecosystem of remembrance: books, documentaries, public plaques, educational programs, and memorials across Paris that keep the victims’ names alive. At the Bataclan itself, visitors often pause at the entrance, sometimes laying flowers or handwritten notes.

Cultural historian Paul Veyrard explained in a recent documentary that remembrance in France has evolved. “These attacks didn’t fade into the background like other tragedies. They reshaped how France talks about radicalization, citizenship, and resilience.”

What This Anniversary Really Means

Anniversaries of trauma are complicated. They bring back the worst of the memories, but they also mark what the country has managed to rebuild. A decade later, France is still asking the same questions Sophie Dias voiced: why this happened, and how to keep it from happening again.

The commemoration isn’t about reopening wounds. It’s about refusing to forget what those wounds represent. And in that refusal, France continues to define how it wants to face its future.